Did You Know About the Struggles of African Americans in Davenport to Educate Their Children?

Local historian Craig Klein has gathered the following information from research in eastern Iowa.

The Colored School Controversy

As in other midwestern states, the struggle for equality in Iowa schools began long before the Civil War. Believing that blacks were inferior to whites, members of Iowa’s First Territorial Assembly enacted a general school law in January l839 that barred black children from attending school with their white peers. As a result, when Iowa gained admission to the Union in 1846, school laws already in place prevented black children from attending the “common schools” established in each county. Paralleling other “whites only” practices sanctioned by Iowa’s early constitution, this arrangement was supported by most Iowans in the late 1840s and 1850s. However, increasingly in the 1840s and 1850s, Iowans sympathetic to the plight of blacks began to question the wisdom and morality of this school law provision. Prompted by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, the debate over equality in Iowa schools became heated in the 1850s. At the constitutional convention of 1857 in Iowa City, delegates favoring open enrollment for all school children met fierce opposition from die-hard opponents of equality. But when it became obvious that neither side would prevail, the convention approved compromise language that mandated the creation of separate, state-supported schools for black children. In the school law of 1858, the state legislature enacted this provision into law.[1]

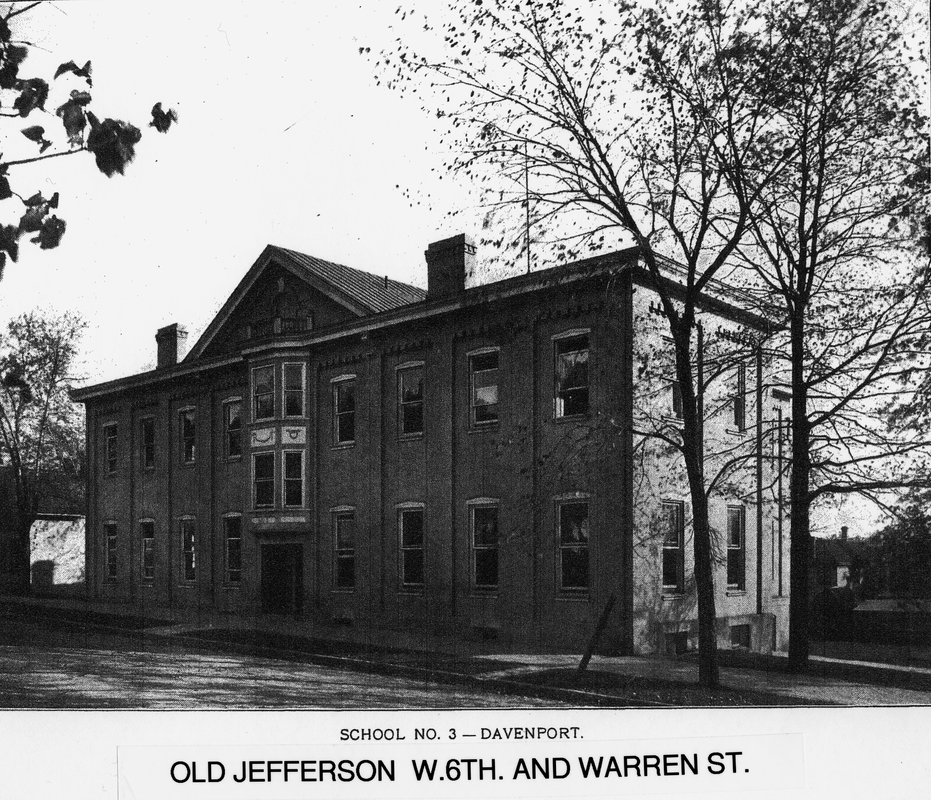

The debate over equality in Iowa schools also resonated at the local level. Charting the course of the debate over this issue in Davenport, Iowa, from 1858 to early 1860, the following news articles and minutes of Board of Education meetings shed light on the controversy that arose over the city’s early “Colored School.” Though Davenport only had a handful of school-aged black children in 1858, their presence became a contentious issue. Formed in May 1858, the city’s first Board of Education apparently sought to resolve the issue by quietly allowing several black children to attend School No. 3 at the southeast corner of Sixth and Warren streets. But in a disparaging June 26, 1858, editorial, the Daily Morning News, a local newspaper with decidedly Democratic and southern sympathies, called on concerned citizens to have these children expelled-a summons that soon bore results. On September 15, 1858, thirty-eight Davenport residents signed a petition asking the Board of Education to expel “some four or five Negroes” then attending the Stone School House at the corner of Seventh and Perry streets. Because the school law of 1858 only allowed for mixed schooling if there was unanimous consent for it in the community, the Board of Education had no choice but to comply: on September 18, 1858, it ordered the expulsion of these children from the city school system.

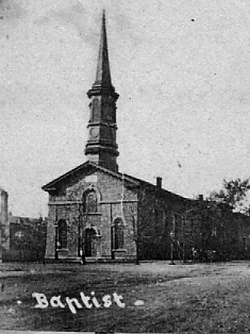

While most citizens acknowledged that the Board had no legal recourse, the decision to remove the children disturbed many Davenporters. Seeking a solution to the crisis, they heatedly debated the issue amongst themselves, arriving shortly thereafter at a consensus to establish a separate school for black children outside the school system. Some residents favored this solution for pragmatic reasons as well: they feared opponents of tax-supported “free schools” would use the controversy to destroy the city school system. Apparently responding to public sentiment, the Board of Education moved on November 8,1858, to establish a separate school for black children in a room in the newly-constructed Baptist Church at the corner of Perry and Fourth streets. But it is unclear if this school ever opened. After failing to establish another separate school in April 1859 (whether it was in the Baptist Church or another location is unclear), the Board moved in late 1859 to establish a “Colored” school in a room in School No. 3 at the corner of Warren and Sixth streets. Opening in early December, this venture soon failed “for want of pupils.” Before mandating an open school system in the early 1860s, the Board reportedly tried one last time in l860 to establish a separate school for black school children in the Baptist Church. But this experiment was short-lived as well.

[1] Amie Cooper, “A Stony Road-Black Education in Iowa, 1838-1860,” Annals of Iowa 48(1986), 113-34

Source: Davenport’s Pioneer African American Community: A Sourcebook, p. 19

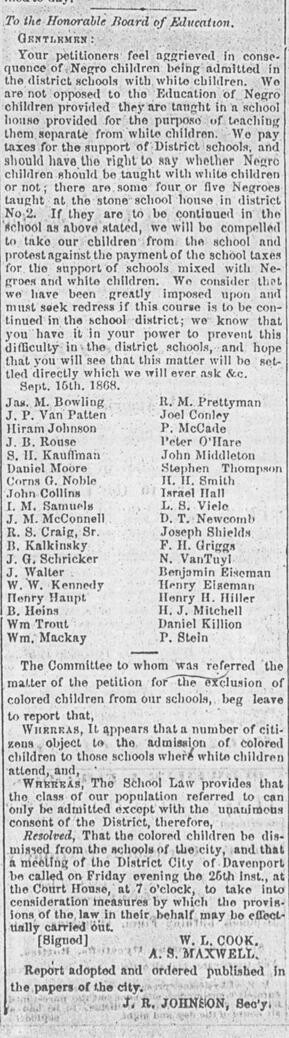

Citizen petition protesting the presence of black children in Davenport public schools. (Davenport Daily Gazette on Sept. 22, 1858) On September 15, 1858, thirty-eight Davenport citizens signed a petition protesting the presence of black children in city schools. Presented to the Davenport Board of Education, this petition appeared in the Davenport Daily Gazette on Sept. 22, 1858, along with copy of the Board’s September 18, 1858 decision to expel several black children from school. (The 1868 date on the petition is in error.)

The Baptist Church - The site of Davenport’s first colored school. Seeking to keep the controversy over racially mixed education out of the city school system, Davenport school officials moved to establish a separate school for black children in November 1858 in the newly-built Baptist Church at the southwest corner of Perry and Fourth Streets. However, it is unclear if this school opened at this time. After school officials failed to establish separate instruction for black children in School No. 3 (later known as Old Jefferson) in December 1859, black children were reportedly again placed in a segregated classroom in the Baptist Church. Probably operating in 1860, this school soon failed as well.

For other Blogs in support of this project, see also:

Did You Know About African American Women's Clubs in Davenport During the Progressive Era?

Did You Know That Frederick Douglass Visited Davenport in April of 1866?

Did You Know That Aeronaut Professor John Byrd Piloted His Balloon from Davenport in August of 1883?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed